Part 1: The Victorian era - 1930

Red velvet cake is the stuff of legends. Whispered tales and conflicting accounts follow it wherever it goes. Today’s incarnation of red velvet cake, an electric red substance that may or may not have a subtle hint of cocoa and slathered with a thick cream cheese frosting barely resembles its humble beginnings as a chocolate cake. So how did it get to be this Franken-color hybrid? For that, we have to take a trip in our Wayback Machine to the origins of velvet cake. (Note that a color wasn’t associated with it yet.)

Velvet Cake

Velvet cake dates back to the Victorian era. According to multiple sources, a velvet cake is simply a cake that has a light, airy, delicate, velvety crumb. “Velvet cakes, without the coloring, are older than Fannie Farmer. Cooks in the 1800s used almond flour, cocoa or cornstarch to soften the protein in flour and make finer-textured cakes that were then, with a Victorian flair, named velvet.” (New York Times) In his 1873 book Dr. Chase Allen Woods describes the newfangled velvet cake: “There is quite a tendency of late to have nice and smooth names applied to things as well as to have nice things hence we have Velvet Cake.” This description sounds just like…well…cake. But back in the Victorian era, not all cake was created equal.

While there were forms of cake that got their lightness from whipping air into eggs (pound, genoise, sponge), the only way to chemically leaven a cake was through yeast. Pre-19th century, the line between cake and bread was blurry. Typically, cakes were distinguished from bread because they were sweeter and included richer aspects like butter and eggs. Additional ingredients such as nuts and dried fruits were included to give cakes an added sweetness and to make them a treat. However, as we see today, the distinctions between cakes and breads were flexible. Today, we may classify desserts such as panettone or brioche as a bread, whereas a traditional fruitcake is a cake. In the 19th century, all of these could have been cake.

Yeast raising made these cakes incredibly labor-intensive, frequently taking more than a day to get through all of the proofing. Additionally, yeast did not come in little packets as it does today. In fact, it wasn’t until 1861 that microbiologist Louis Pasteur published his discovery of yeast. (Fun Fact: His work on killing unwanted organisms in wine also led to the creation of pasteurization.) Bakers needed a mother yeast strand, typically in the form of uncooked starter from a previous baking project or from the yeast taken from beer and other fermented drink or risk the flavor of a wild yeast strain. (Wild yeast is gathered simply by making a wet dough or batter from water and flour and leaving it sit to allow the wild yeast to find the space to grow. Environmental factors are important; it can't be too hot, too cold, or too dry or the wild yeast won't be available or won't prosper. And the flavor is highly variable.) Bakers were desperate for a way to replace yeast rising with something faster and more consistent.

The first attempt at a leavening substitution was potash (AKA pottasche, pearlash, potassium carbonate, salt of tartar, or carbonate of potash). Potash is a product made by pressing water through wood ash to create lye and then evaporating the water out. At first, it seemed to be a good substitute. However, it was known to leave an often-undesirable smoky flavor. Potash also didn't interact well in foods with a high-fat ratio (such as cake) as it would leave behind a soapy taste. As the Spruce Eats points out, this is unsurprising, as the two main ingredients in soap are lye and fat—a fact I learned from Fight Club.

In 1846, baking soda happened. Baking soda, when combined with an acid, such as vinegar, produces carbon dioxide. When used in a batter, you get a cake that has instant leavening with no soapy or ashy aftertaste; it was an immediate hit. We still use baking soda today for baking, cleaning, and science projects. It is a wonderful ingredient! The only drawback is that for it to create its bubbles, you need a reliable source of acid. While today store-bought buttermilk and vinegar are consistent in their acidity, it was hard to be sure in the mid-19th century just how acidic your buttermilk was, or how strong a reaction you would get.

Enter baking powder. In 1856 the first viable baking powder was patented in the US. Made from an extracted acid compound and baking soda mixed together, baking powder was truly a “just add water” product. When incorporated into any liquid, the baking soda and the acid in the powder would react with each other, causing carbonation.

These products gave rise (pun intended) to the then entirely new genre of velvet cake.

When velvet cakes first came on the scene, they still contained many of the added flavors and ingredients of the bready cakes of yore. They would include things such as nuts and dried fruit for sweetness. They were baked in long pans that we would now consider loaf bread tins.

Gradually, however, added sugar, sweet frostings, and fillings that we consider traditional to other forms of the different popular types of cake began to take over as the main sweetening agents. One of the first, and still most popular additions, was chocolate. Chocolate was very expensive, so initially, “chocolate cake” meant a yellow cake that had chocolate frosting or filling.

The Red Color

Chocolate began being fully incorporated into cake as early as 1781 (Brave Tart) but didn't start to become really popular until 1893 when the April issue of Table Talk published a recipe for a fully chocolate "Devils Cake!" This was a moist, decadent cake consisting of a paste made from chocolate and boiled milk, and people began to incorporate chocolate into their cakes. Chocolate was still expensive, however, and as time went on, substitutions for the cheaper cocoa powder began to be made.

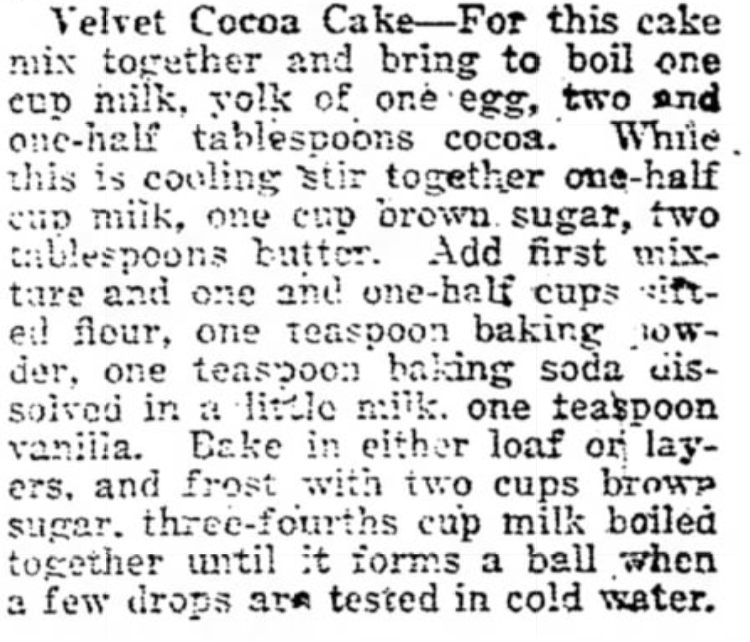

In 1911, the first recipe for “Velvet Cocoa Cake” with a thick boiled brown sugar frosting appeared in the Ohio Telegram.

Just a few years later, in 1914, the same recipe started showing up in newspapers across the US, and a craze had started. Through the nineteen-teens and twenties, the chocolate cake craze only continued to spread. And people began to comment on the red-brown color these cakes sometimes turned. But not all the chocolate cakes turned red. Recipes spread, and the tale of red cakes grew in popularity through the 1920s. People all across the United States wanted to try their hand at making not just a chocolate cake, but a red cake. And at this point in the research, so did I.

The Re-Creation

The red or "devils" moniker came from a combination of using red sugar (brown sugar), and the red-brown hue the cake would take on when the chocolate and acid combination interacted. Chocolate, particularly raw cocoa powder, naturally contains red anthocyanin in it. When combined with an acid, it intensifies the anthocyanin notable red coloring. Coincidentally, this level of acid either from vinegar or buttermilk, was also necessary for baking soda to activate. This meant that cocoa cakes that used vinegar and baking soda as opposed to baking powder had a more noticeable red color.

Since names such as red cake, cocoa velvet, devil cake, and devil’s food, began to be used interchangeably, It is important to set up the distinction between a devil's food cake, red velvet cake, and other varieties. While the styles are all similar, there are important distinctions.

For this purpose, a devil’s food cake is a cake that traditionally involves brown sugar and chocolate, giving a deep black color. By contrast, a red velvet cake must be made with cocoa powder, an acid liquid such as buttermilk, and baking soda as the leavener, all reacting to give the cake a rich red-brown color.

This important distinction helped in sifting through the old recipes and figuring out which ones count as “red velvet” and which are simply chocolate cakes.

I searched through several recipes, including one recipe from 1915 actually calls for fermenting the baking powder leavened cake overnight to produce a genuinely red color.

This recipe from 1924 mentions the chemical interaction that gives its cake a red color.

I settled on a 1927 recipe, first appearing in the Richmond Item, for “Red Devil’s Food.”

While its title is that of devil's food cake, it carries all the hallmarks of red velvet. The recipe uses a buttermilk and baking soda base and gives the baker the option of cocoa powder and chocolate. It even calls for topping it with a traditional ermine (boiled milk) buttercream frosting. The recipe also had some of the most specific instructions for baking, actually giving a baking time and temperature, a true luxury when you work with old recipes.

I opted to use cocoa powder when making this recipe. I used raw cocoa powder, as it has the highest amount of anthocyanin. I was lucky and actually managed to find a large bag of raw cocoa at Costco. Still, Costco giveth, and it taketh away; you never know if they’ll have a product the next time you come to the store. If you are at the grocery store, a basic cocoa powder such as Hershey’s will do; it just won’t result in as deep a red color. But be sure your cocoa powder isn’t a Dutch or ‘special dark’ cocoa powder. There are important differences between the raw, processed, and Dutch. Raw cocoa powder is made from the raw, unroasted beans that have been crushed and had the cocoa butter removed. Heat has never been applied to it, which is why it retains the most anthocyanin. A typical processed cocoa powder, such as Hershey’s, has been roasted during the process, removing some of the anthocyanin and the resulting less red color than raw cocoa but leaving most. Dutch press, or ‘special dark’ cocoa, has gone through an alkalizing process, which gives the cocoa powder a much darker tone and prevents it from reacting with the baking soda because it has already been alkalized, so it will give a cake little to no red color.

Raw vs Dutch Cocoa

While the recipe I used is for a layer cake, I had my one-year-old son's birthday coming up, so I opted to make them as cupcakes and serve them at the party. The recipe transferred beautifully to cupcakes, and the cake was incredibly good. For…ahem…research purposes, I also made a batch of straight chocolate cupcakes. When placed next to each other, the red color is starkly noticeable.

Red Velvet on left, chocolate cupcake on right

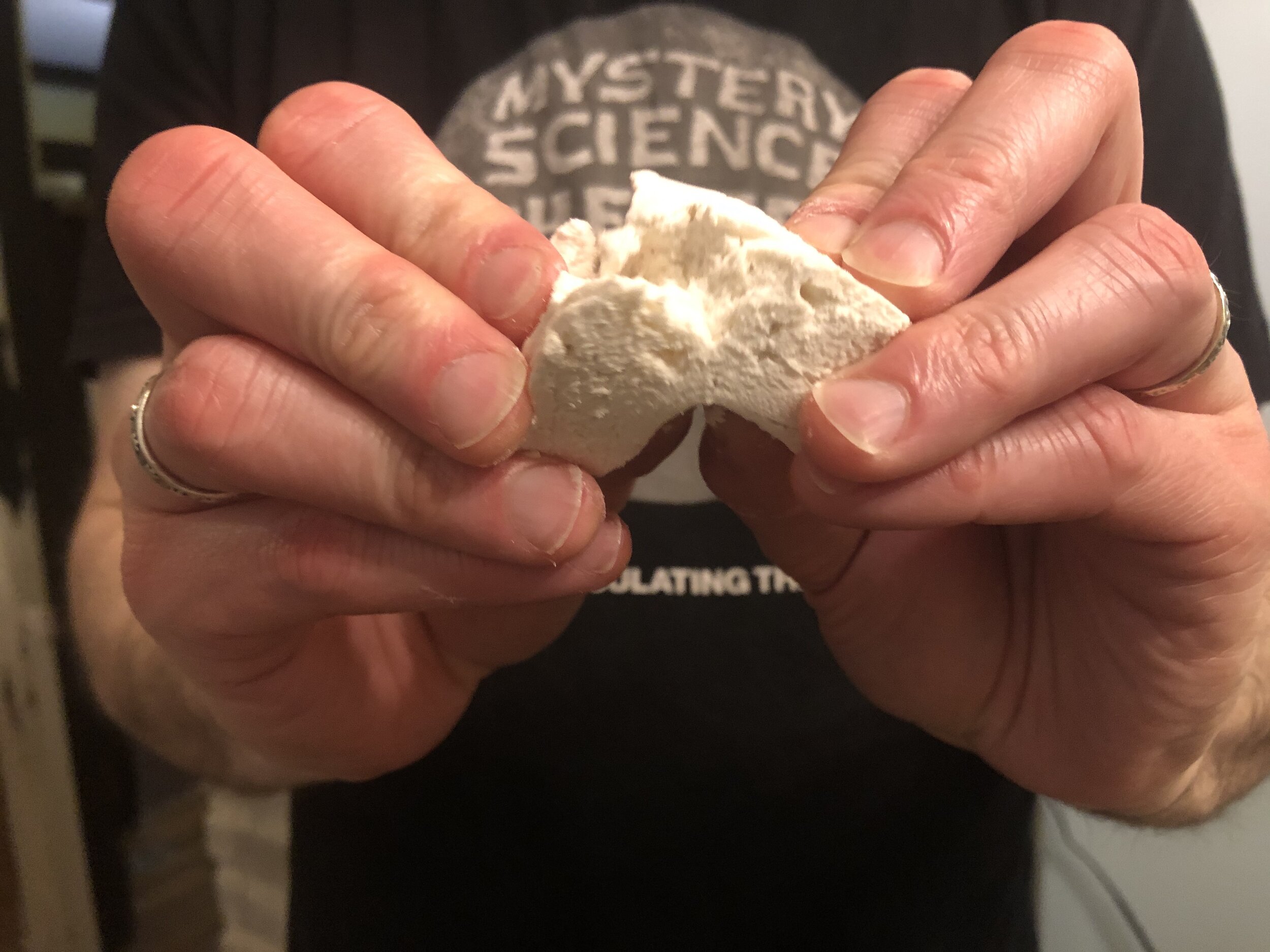

These red velvet cupcakes were tender and definitely had a velvety crumb. They also had a noticeably more chocolate flavor to them than a modern red velvet cake. While this cake contains 1 cup of cocoa powder, many modern red velvet cakes contain as little as 2 tablespoons of cocoa powder. That is more of a cocoa “blessing” than a cocoa flavor, in my opinion. The cocoa flavor is replaced by a truly exorbitant amount of red food dye. More on that in Part 2.

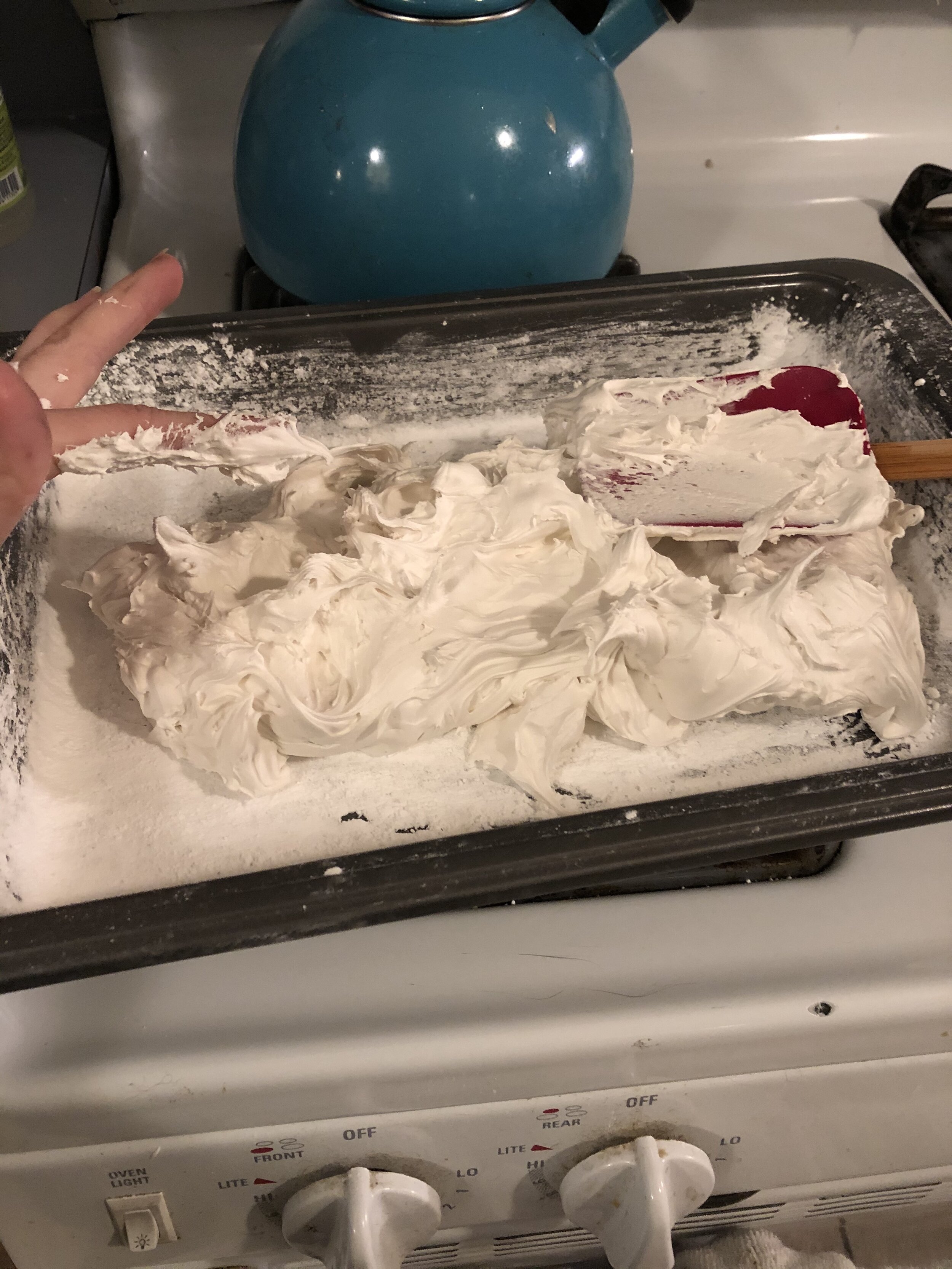

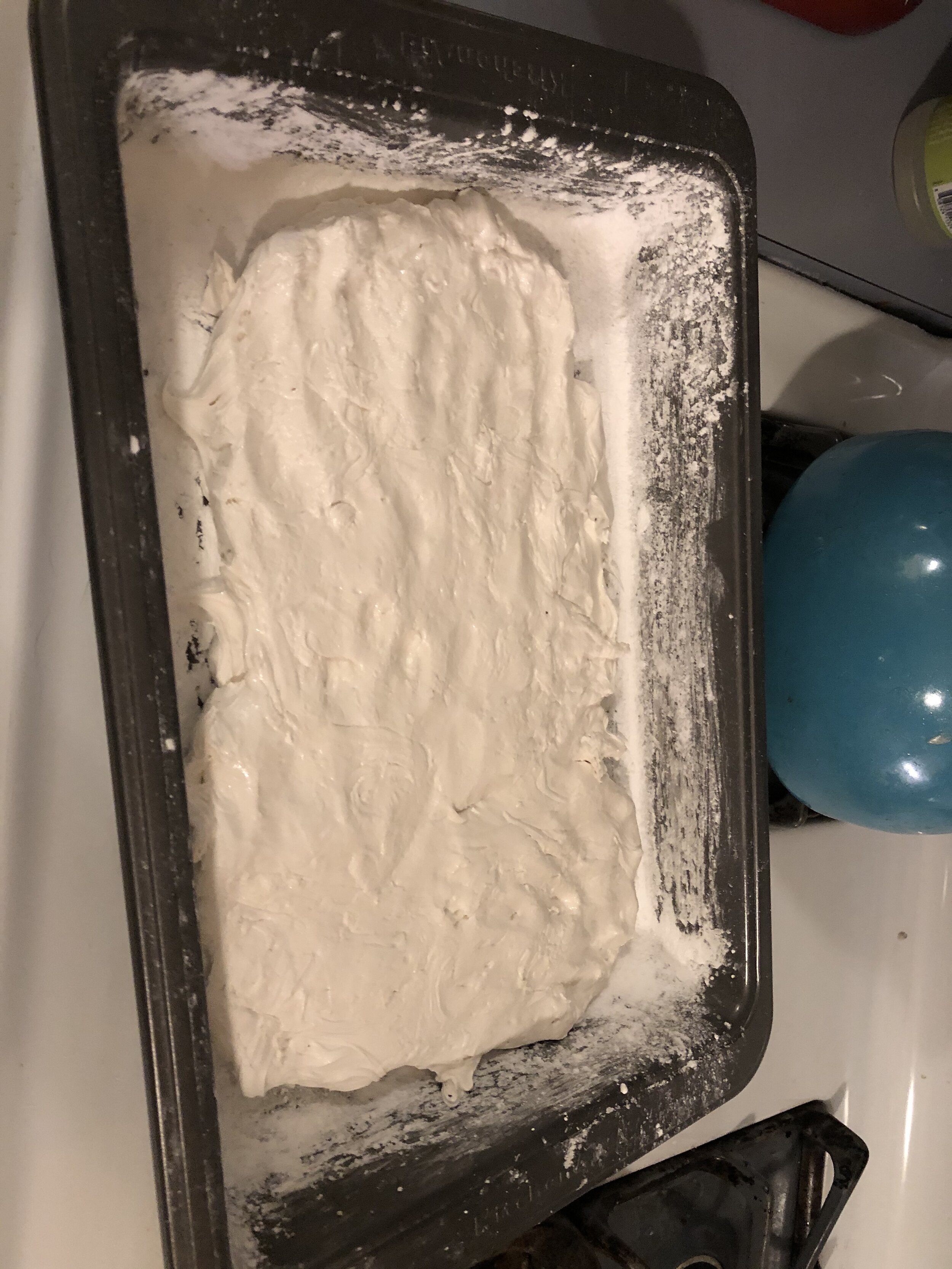

I topped my cupcakes with the recommended ermine frosting. I had never made it before, and it was absolutely delicious. It was lighter and less sweet than its American counterpart, more consistent with that of meringue buttercream. And while it is similarly labor and time-intensive to make, it is significantly less finicky, so I was able to do other things while making it. These cupcakes and frosting were a big hit, and I would definitely make them again.

Join us next time, for red velvet 1930-modern day featuring artificial coloring craze, racism in America, and corporate takeover. Red Velvet – Dye Harder

1927 Red Velvet Cake

A soft tender crumbed cake adapted from a 1927 recipe for “Red Devils Food.” This cake pairs well with an ermine frosting.

Servings: 24 cupcakes

Cook time: 10 min prep, 20-30 bake

Ingredients:

1 cup room temperature butter

2 cups of sugar

4 eggs

3 cups flour

1 tablespoon baking powder

1 teaspoon salt

1 cup buttermilk

1 cup boiling water

1 cup of cocoa

2 teaspoons baking soda

2 teaspoons vanilla

Instructions:

1. Cream butter and sugar together.

2. Add eggs.

3. Mix flour, baking powder, and salt. (three times as per the incredibly specific recipe)

4. Alternate adding the flour mixture and buttermilk to the creamed butter and sugar.

5. Pour boiling water and cocoa together. Mix quickly.

6. Add baking soda and mix until thick.

7. Cool slightly, then add to cake.

8. Mix thoroughly and add vanilla.

9. Bake at 350 for 30 min as layer cake and 20 min for cup cakes.