In the Middle Ages, marshmallows continued to be used throughout North Africa, Europe, and Asia. As mentioned in the last post, the marshmallow was used as an ingredient in halva. It was also steeped in water to make a tea and continued to be used for a variety of medicinal purposes. In medieval Europe, the root of the marshmallow was candied and eaten. This treat would have been similar in texture to candied ginger root. While this is undoubtedly a sweet treat, it is not a marshmallow.

The true precursor to the modern marshmallow started in France as a confection known as pâte de guimauve. It arrived on the scene between the late 1700s and early 1800s. The oldest recipe I found dates back to 1757. Pâte de guimauve is a French confection said to have originally been comprised of sugar, egg whites, and marshmallow root extract. The mixture was functionally an unbaked meringue left to harden. The addition of marshmallow root gives it a somewhat soft and chewy texture. Often other flavors, such rosewater, would be added to the mixture. Rosewater was an incredibly popular flavoring because at the time it was a by-product of making rose petal perfume. Likewise, orange blossom water (which I will be using my recreation) was a byproduct of making orange blossom essential oils. Our ancestors did not like to waste things.

Perhaps unsurprisingly given its medicinal history, pâte de guimauve was originally developed as a health lozenge, with many recipes showing up in books of medicine and giving instructions as to when to take them (Eléments de Pharmacie théorique et pratique). This early French marshmallow was used to relieve throat aches, as well as being ‘pectoral,’ or related to chest or lung disease (A Cyclopædia of Several Thousand Practical Receipts), the same medicinal purposes for which it had been used for thousands of years. And, just like in previous eras, the marshmallow became a popular confection.

This 19th-century popularity caused the demand for the marshmallow to skyrocket. There were only two problems: it was time-consuming, and expensive to make. The process of extracting the marshmallow sap, as we know, takes 12 hours. By the late 1700s, this hasn't changed. Instructions for making marshmallow candies still include 12 hours of soaking and prepping the extract.

At this point the meringue still has to be made by hand-beating egg whites, adding a hot sugar marshmallow syrup, and then continuing to beat the mixture to incorporate and keep the meringue light. Again, this was all done by hand. The mixture would then take at least another six hours to properly set. AND THEN the pâte de guimauve would still need to be cut and shaped. At this point, pâte de guimauve became a two-day long endeavor for confectioners. If anything were to go wrong during this process, it would result in the entire batch being ruined, and the potential of up to two days of wasted efforts.

Confectioners were under pressure to produce a fluffy gummy treat for the masses. This led to the addition of gum arabic, a product made from acacia tree sap, into the mix. Adding the gum provided much more stability, giving it body, and more bounce than just the marshmallow root could provide. Additionally, the preparation of gum arabic did not take nearly as much time as the marshmallow root.

Most sources claim that the original pâte de guimauve consisted of exclusively marshmallow (root), sugar, egg whites, and flavoring. I disagree. All the recipes I have found, even those dating back to the 18th century (which I'd like to note is earlier than many sources even think pâte de guimauve existed) include gum arabic. Is it possible that there were versions without this additive? Sure. But it seems the most common and documented way to make pâte de guimauve was with gum Arabic.

While the addition of gum arabic made the recipe faster, easier, and more reliable, this ingredient came at a price. Literally. Gum arabic was incredibly expensive and had to be imported from Southern Arabia and Western Asia. And while it did ease the reliance on marshmallow root to form the confection, confectioners continued to use the root, which meant the process still took two days to complete.

With the price and production time crushing on confectioners, it became harder and harder for them to keep up with public demand. Almost a century after the introduction of pâte de guimauve, the late 1800s saw the invention of the Starch Mogul system of candy production. The system was used by coating candy molds with a layer of starch powder, such as corn or potato. This allowed a more liquid substance to be poured into the candy molds, and once set, extracted without the substance sticking to the mold and falling apart. This method gave confectioners the ability to create larger volumes of marshmallows as they no longer had to cut and individually shape each piece. This in turn made marshmallow far more accessible to the general public.

The Re-Creation

Luckily for me, there is not a lot of guesswork that goes into a classic recipe for pâte de guimauve. Unluckily, they are mostly in French. Luckily for me again, my mother majored in history and French in college, and currently works as a technical writer! What more could I ask for?

The following recipe is the one my mother kindly translated for me. Everyone say thank you to mama Nichols! (And if you have complaints on the translation, please bring them up with her.)

I found a variety of recipes that I could have chosen to make the marshmallow. I chose this one, because of all the recipes it seemed to contain the most detailed instructions. For example, this recipe still relies on the traditional meringue method of mixing your egg whites into the sugar syrup bit by bit. Other recipes were not as clear, some would simply say “make a meringue” and leave it at that. Since we are going for a true reproduction, I wanted as much instruction as possible.

That being said, I did end up making a few modifications to the recipe.

For this attempt, I used dried marshmallow root, not fresh. As I did this in January in Pittsburgh, fresh marshmallow root could not be found. In order to rectify this, I needed to find out what the weight difference between dried marshmallow root and fresh was. If I did a straight weight to weight substitution I could end up with way more marshmallow than I intended. I finally settled on using the weight of dried vs fresh ginger as a comparison, as they are similar roots. I found the weight difference is that of 1 to 4, dried to fresh, so I quartered the amount of marshmallow, giving me 31.25 grams.

Next, I only had access to powdered gum arabic, not chunked. I thought this would be more of a problem than it was. Powdered gum arabic is just the chunks that have then been crushed into powder form. It dissolves faster and easier than its whole form. So yes, in a way I am taking the easy way out by using this, but also it is a straight weight to weight equivalent, and since 19th century France is ahead of 21st century America when it comes to cooking and their ingredients are in weight (not volume) it was an easy conversion.

My next question when approaching the recipe was about the sugar. While France is known for their excellent use of sugar, there is a bit of a complicated history when it comes to France’s sugar source. The brief explanation is that during the reign of Napoléon the British stopped the import of sugar into France. Sugar cane became too expensive and difficult to acquire, leaving France without a key ingredient for their baked goods. Then, in the early 1800s, Napoléon was presented with sugar made from sugar beets. He was so impressed he had thousands of acres planted with sugar beets, and sugar was back on the shelves and more attainable than ever. However, after his death sugar cane once again became available for purchase, and after a peak in the 1830s sugar beet production went back down. As this recipe is from 1847, it could have been made with beet sugar or cane sugar. I am using cane sugar as the sugar is the prominent ingredient and flavor. However, either will work and either will give you a traditional white marshmallow.

Additionally, the instructions are very clear about using fresh eggs, and whipping enough, so as to get a pristine white confection. That snowy characteristic was seen as what one should strive for with marshmallows.

The final ingredient is orange water for flavor. I personally like rosewater but no one else in the house does. So I went with orange blossom flower. I did have a bit of trouble finding it but eventually found it in the cocktail section of my grocery store. It can also be ordered online. The marshmallow then tasted like soap. So I also made an unflavored batch. This also let me tell if the offending marshmallow root flavor would show through.

Once I had gathered all the ingredients, it was time to start the recipe.

First, I made a batch of the marshmallow extract, starting it the night before so it would be ready to go the following morning. One of the big differences here is that the instructions also say to boil the marshmallow root with the gum Arabic before straining it the entire mixture. The instructions were a little vague, but after consulting other recipes (and messing up two prior batches) it appears you should not strain the root out until you have dissolved the gum arabic. While cold infusion extracts mostly mucilage, cooking it also extracts the starches as well, which helped the marshmallow set properly.

Cook this mixture for about 30 minutes.

Next, use a cheesecloth or mesh sieve to strain out any lumps and the marshmallow root. And then cook to what we translated as “syrup.” I interpreted this as to mean hardball stage. It is going to look like a syrup the whole time, but you need it to be able to hold its form once cooked.

Once the liquid is at hardball stage, you use the whisk to beat in your eggs (already whipped to soft peaks) into the liquid and keep whipping the marshmallow and egg mixture. I found it easier to do with a handheld beater. But if you want to do it with a whisk, more power to you. Now, despite what the instructions say, do not drop it on the back of your own hand. It will hurt, you will get a burn, and you will think about it every time you see your hand. Trust me on this one.

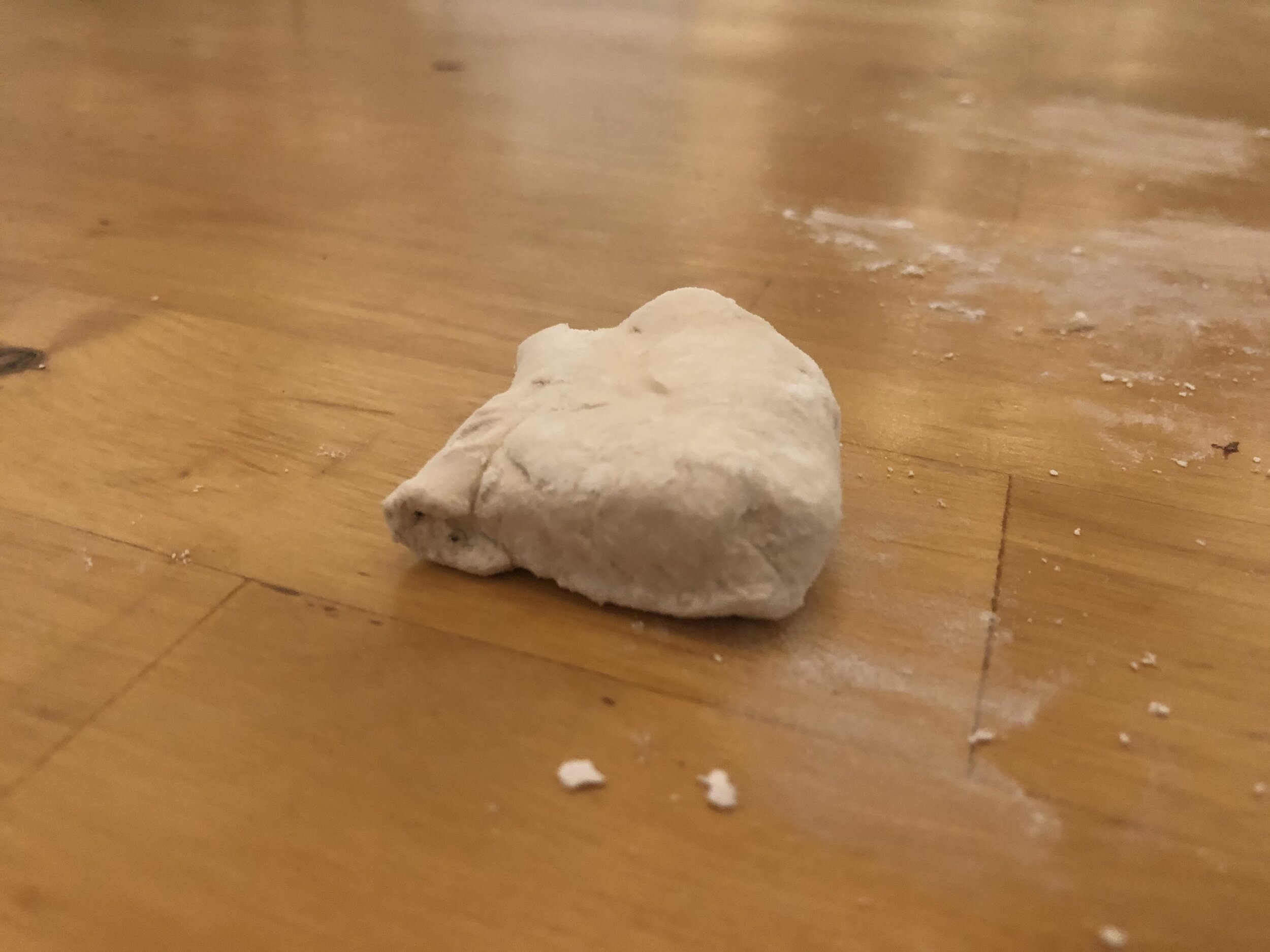

mmmm….marshmallow….

Another way I would describe the right consistency is to cook it until it holds its form and begins to leave a trail as the beaters move through it. You can also drop a little onto your marble/baking sheet to see how it holds up.

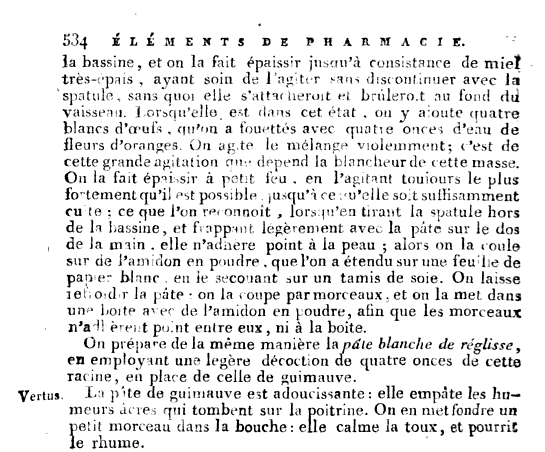

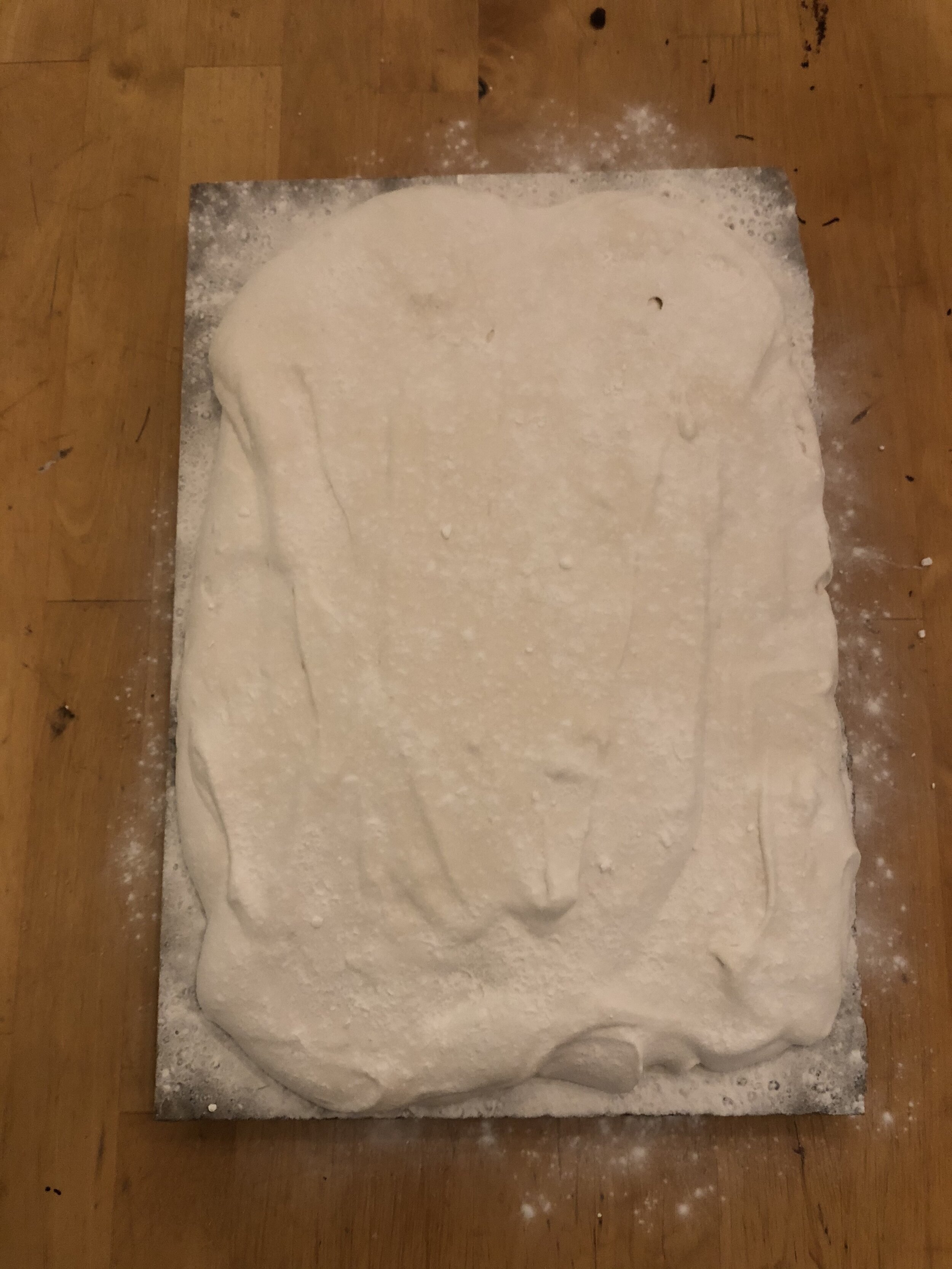

Once the pâte de guimauve has reached the proper consistency, the directions say to pour it onto a powdered marble slab. You can purchase this item at most kitchen stores or online, but I’m going to be honest, that is a waste of money. You can usually get a scrap piece of marble or granite at a lot of building materials recycling center, or contact a local countertop manufacturer. I found one for a mere $7 as opposed to $60 slabs found at boutique cooking stores. This will get you a thicker piece, for a lower price. The reason you use marble or granite is that it remains cool and helps the mixture set quickly.

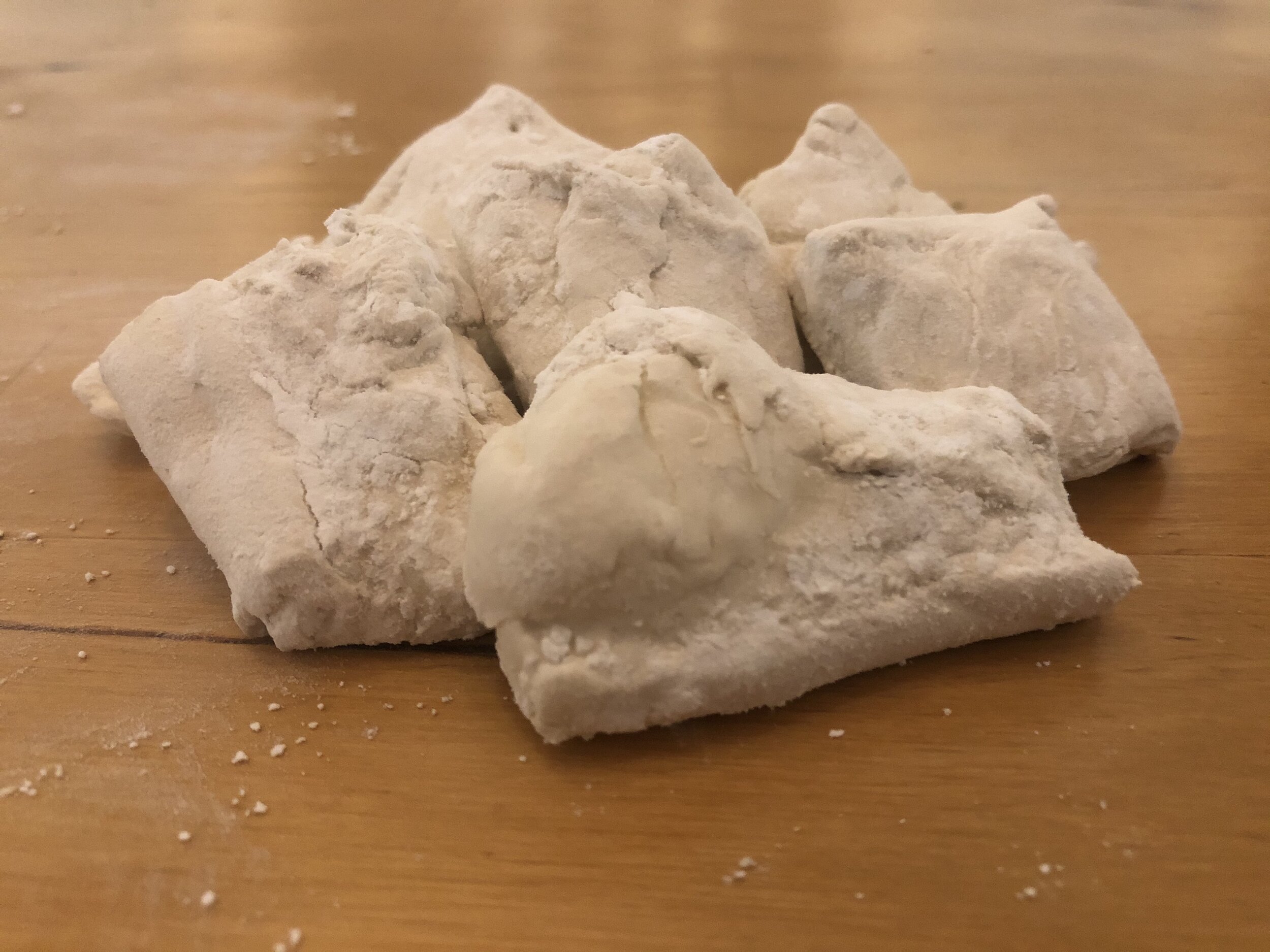

Finally, pour the marshmallow onto a slab that has been coated in powdered starch or powdered sugar. Top it with more starch and let cool on the slab for at least six hours. The large hunk should then be cut into squares and served. Alternately, you can pipe individual pieces onto or marble slab, or onto parchment paper, though the parchment paper will take more time to cool.

Finally, pour the marshmallow onto a slab that has been coated in powdered starch or powdered sugar. Top it with more starch and let cool on the slab for at least six hours. The large hunk should then be cut into squares and served. Alternately, you can pipe individual pieces onto or marble slab, or onto parchment paper, though the parchment paper will take more time to cool.

You will then have your 19th-century French marshmallows! Pate de guimauve will not remind you very much of a modern marshmallow in texture. It is noticeably softer and malleable, and does not hold its shape after being cut. I would recommend piping individual pieces instead of one large sheet so a skin forms on them for easier consumption. The flavor is much more similar to a modern marshmallow, however in the batches I made without an added flavor, It was noticeably earthy. I enjoyed it, but I can see how others might not.

EDIT: Pâte de guimauve can also be translated as Pâté de guimuave. This changes the name meaning from “dough of marshmallow” to “paste of Marshmallow” and the pronunciation from ‘pat’ to ‘pat-ey’. Pâte de uimauve, or “dough of marshmallow” seems to be the correct translation, although arguably either is an accurate description.

Classic Pâte de Guimauve (Gelatin Free Marshmallow)

Translation of a French Pate De Guimuave recipe from the 1800s. Lovingly translated by Mama Nichols. It creates a light fluffy confection almost exactly like a modern marshmallow. Additionally, this recipe contains no gelatin, making it suitable for vegetarians, though not vegans as it contains eggs. If you don’t like orange water you can omit, or sub for a different flavor.

This is the original recipe, translated. Any added instructions are italicized.

Cook time: Way too long

Servings: Way too many (We recommend halving the recipe), I recommend halving or quartering the recipe

Ingredients

· 125 grams marshmallow root (cleaned of all dirt) (or 31.25 grams dried)

· 1000 grams gum Arabic (very white)

· 1000 grams white sugar

· 2000 grams filtered water

· 12 egg whites

· 90 grams orange flower water

Instructions

1. Soak the clean marshmallow root in water for 12 hours. Do not squeeze the roots. Drain the soaking water into a medium saucepan.

2. Warm the soaking water. Break the gum Arabic into small pieces and melt them in the warmed liquid. Bring the gum arabic and marshmallow liquid to a low boil. It will take about 10-15 to dissolve all of the gum arabic. Stir consistently.

3. Place sugar into a large, wide saucepan. Strain the gum arabic liquid through fine cheesecloth into the pan.

4. Whip the egg whites to soft peaks with a wire whisk. Add the orange flower water.

5. Simmer gently over low heat, stirring constantly with a wooden spatula, until the liquid is reduced to the consistency of extract (syrup?). Bring to a simmer, and cook until hardball stage is reached.

6. Using the whisk, in portions, add the whipped egg whites to the liquid. Continue to mix with rapid strokes until all the egg whites are incorporated and the mixture forms a paste that no longer clings to the wooden spatula and when a bit is dropped on the back of the hand, it doesn’t stick. I recommend using an electric hand beater to keep beating once all egg whites have been added.

7. Remove from the heat.

8. Dust a flat marble surface with a layer of powdered starch. Pour the marshmallow paste onto the starch-covered marble. Cover with more powdered starch or powdered sugar.

Notes from the recipe:

· The whiteness of the candy depends on the freshness of the eggs, the quantity of air introduced during the whipping (“introduced by the accelerated movement of a wicker broom,” which I interpret to be a wire whisk), and by sustaining rapid whipping until the time that the paste/batter no longer clings to the whisk.

· Almost always, to have the whitest candy, “we remove the marshmallow root and dissolve the gum Arabic and sugar in pure water.”