Starting as a delicacy designated exclusively for ancient Egyptian royalty, the marshmallow has developed into one of the most widely consumed treats available. What cold winter’s hot cocoa or summer campfire would be complete without some of the white fluffy stuff? It isn’t just the sugary sweet taste that people cling to, it’s the sentimentality that comes with it. In the words of Ray Stantz, from the classic film Ghostbusters, the marshmallow is “…something I loved from my childhood. Something that could never, ever possibly destroy us.” Considering the enduring love for these squishy white confections, it’s amazing how little the current treat resembles its original form.

The Plant

The marshmallow has changed its shape many times since its inception. Perhaps the biggest change is that the marshmallow treat today does not actually contain any marshmallow plant. Yes, there is a marshmallow plant; no it does not grow marshmallows. Its Latin name is Althaea Officinalis and is a member of the Malvaceae family. As a group, plants in this family are called “mallows.” The mallow family includes more than four thousand species of herbs, shrubs, and trees. Hollyhock and hibiscus are both members of the mallow family. Althaea Officinalis grows primarily in marshy wetlands, which is how it got its name, marshmallow.

Every portion of the marshmallow plant is edible. For example, the flowers, stems, and leaves can all be used to make salads. But the main portions of the marshmallow that are consumed are its root and leaves. This is because these parts contain medicinal properties that have been popular throughout history.

Beginning around 9th century BCE, the Greeks used marshmallows to heal wounds and soothe sore throats. A balm made from the plant’s sap was often applied to toothaches and bee stings. The plant’s medicinal uses grew more varied in the centuries that followed: Arab physicians made a poultice from ground-up marshmallow leaves and used it as an anti-inflammatory. The Romans found that marshmallows worked well as a laxative, while numerous other civilizations found it had the opposite effect on one’s libido. By the Middle Ages, marshmallows served as a treatment for everything from upset stomachs to chest colds and insomnia. (Mental Floss)

Marshmallow could be used for just about anything. Both the ancient Greek physician Dioscorides and the Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder used marshmallows in similar ways. Dioscorides describes marshmallows as useful “boiled in melikraton [honey wine] or wine or chopped on its own, it works against wounds, tumors of the parotid gland, swellings in the glands of the neck, abscesses, inflamed breasts, inflammations of the anus, bruises, swellings, tensions of the sinews…it worked also against dysentery, blood loss, and diarrhea” (Hippocratic Recipes 264). Marshmallow was so popular for treating ailments, its name Althaea is the Greek word for “healer.” Officinalis is medieval Latin used to describe botanical plants used for medicine and herbalism. Its botanical name literally means “healing medicinal plant.”

In traditional Chinese medicine, marshmallow is used to treat coughing, edema, the common cold, and bronchitis (Me & Qi). The thought is that the marshmallow plant helps to cool the blood, helping to clear inflammation and infection, which makes it useful for treating all these maladies. European and other western cultures have similar ideas about marshmallow’s effectiveness. Marshmallow is thought to contain chemicals that help heal and decrease inflammation. It is thought to coat and create a protective layer on parts of the body it is applied to (Web MD). The marshmallow root, in particular, contains a mucilaginous sap that, when ingested, creates a protective coating. It is this extracted sap that was used to form the original marshmallow candy and hold the confection together.

Origins in Ancient Egypt

The original marshmallow confection dates back to 2000 BCE in ancient Egypt. There are multiple references to a mallow candy being made for the consumption exclusively for the royalty and gods. This limited consumption is likely due to the excessive amount of labor and expense incurred when producing the confection.

Little is known about the process that went into making the original marshmallow. There are a few records that tell us what ingredients were used. We know the ancient Egyptians would extract the sap from a marshmallow plant. Different sources say this was done by “squeezing,” (National Confectioners Association) but this is probably not likely, as the marshmallow mucilaginous sap is extracted from its roots, and even freshly harvested the roots would not have provided much liquid. It would have been similar to trying to squeeze the juice from a portion of ginger without modern-day equipment. It is more likely that the roots were crushed, and then soaked and boiled to extract the sap.

We know that the sap was mixed with honey to form the base of the treat, and to sweeten it. We also know that nuts and sometimes grains were added to the confection. There is no indication of how these would have been combined, such as if the grains or nuts would have been ground, forming more of a cake-like texture, or added whole, having the honey and marshmallow form a sort of brittle. In fact, descriptions of the texture of the confection vary. Some sources refer to the confection as a “gooey treat,” whereas others refer to it as a cake. But the truth is, we just don’t know.

One source postulates that the Egyptian marshmallow was the precursor to the Mediterranean candy "halva." The term in America is most commonly used to refer to a chewy candy made from nut butter or ground grain and sweetened with sugar or honey (Yesterdish). However, halva is also a word that can be used to describe a range of sweets, from pressed cake to brittle to filled cake-like confections. (The Oxford Companion to Food). The oldest written recipe for halva is in the early 13th century Arabic Kitab al-Tabikh (The Book of Dishes), making it 3300 years after the earliest known documentation of Egyptian marshmallows. That being said, I think it is very possible that the Egyptian marshmallow was, if not a precursor, a version of what we now call halva. We know that Egyptian marshmallows and halva contained similar ingredients: honey, nuts/seeds, and sometimes grain. We also know that some older recipes for halva did include marshmallow plant extract in them. But while it’s possible that marshmallow and halva developed together, that doesn’t help us determine what was the consistency of the original marshmallow.

The Re-creation

This was an interesting recipe to try to emulate. As I mentioned, there are no existing recipes for the sweet marshmallow confection that the ancient Egyptians ate. We know what ingredients were used: marshmallow root and honey mixed with nuts, seeds, grains, and fruits. We know some sources refer to it as a “halva,” but we also know that “halva” can be a term used to define a variety of desserts. The delicacy has been described as a cake, a brittle, and a chewy confection. We really don’t know what style of treat it was. While this makes things even more difficult, it also gave more opportunities for interpretation.

First, I considered doing a honey taffy, such as this one. One of the oldest forms of candy was created by taking honey, boiling it, and letting it dry into a taffy-like consistency. This would be appropriate in terms of ingredients, but I wasn’t convinced this was exactly what the ancient Egyptians were creating. Further research showed there were many kinds of honey treats consumed by the Egyptians. Often these were formed into balls and mixed with nuts and grains. I completely encourage anyone who wants to, to incorporate marshmallow root into one of these traditional candies. Still, it seemed like adding the marshmallow extract to the taffy without some other binder could go wrong at several steps and wasn’t likely how the ancients incorporated it, given their technology.

Next, I considered halva. As discussed, halva can refer to a variety of confections, but for simplicity’s sake, I am using “halva” to refer to the tahini candy. In a basic halva recipe, you have three ingredients: sugar, water, and tahini. At first glance, you could simply swap the water for an infused marshmallow liquid. But we know the marshmallow candy used honey, not sugar. When making honey halva, you typically don't add liquid. It would require more effort to create a new cooking time, and properly boil the honey and liquid down to the softball stage. And frankly, I don’t like tahini or halva that much and therefore didn’t want to put in the extra effort.

Finally, I landed on a honey marshmallow nougat. Nougat is an ancient sweet, similar to a meringue. Both of their bases come from sugar syrup and egg whites. A nougat, however, has a much higher sugar to egg white ratio than a meringue. Because of this, nougat tends to be much chewier than its meringue cousin. Nougat also is not baked when turned into candy. Nougat predates the meringue by at least several hundred years; the first baked meringue recipe does not show up until the 1600s. Versions of nougat are thought to have originated in North Africa and Egypt, including some with sesame seeds. In fact, they resemble halva and match all of the points we know about Egyptian marshmallows. While it is said that many of the middle eastern recipes for nougat did not contain eggs, written recipes dating back to the 15th century include eggs, and Roman recipes dating back to the first century do, as well.

There are two main methods for making a nougat. The first is the modern method, of bringing a sugar syrup to soft ball stage, pouring the molten sugar over your whipped egg whites, and beating until completely formed. This tempers the eggs, making them safe to eat and hold their shape. While this method is a bit temperamental, it only takes about 15 min to make. This, however, would make things far too easy, so of course, this is not the process that I used.

I applied a traditional method of bringing the sugar syrup to soft ball stage, then using a whisk to slowly add in the egg whites. Using this method, you then cook and stir your nougat for 45 or more minutes. It is time- and labor-intensive but it is the way ancients would have done it.

In my first attempt at this method of making nougat, I did not boil long enough because the baby woke up from his nap. I thought it would be fine. It was not fine. I ended up with a much more caramel like consistency. So I decided to turn the failed nougat into filling for chocolates.

Yummy Marshmallow Nougat Chocolates

It took multiple more attempts (and trips to the store for more ingredients) before I figured it out. Slow and steady is the name of the game. The ingredients are simple: egg whites, honey, marshmallow extract, and the fruit and nut of your choice. But if you try to rush the process, you will not end up with a complete product.

At the end of the week I ended up with numerous batches of nougat, but finally found a recipe I was happy with. This nougat looked and tasted different from any nougat I had ever had before. I found that the addition of the marshmallow makes the nougat a little spongier, I personally very much enjoyed it. Marshmallow nougat also retains a darker amber color when compared to a traditional honey nougat, which lightens as you cook it. The marshmallow nougat was a resounding hit and we found good loving bellies for all the batches I made (even the chocolate one).

Traditional honey nougat on left, marshmallow honey nougat on right

Honey Marshmallow Nougat

Based on the descriptions of the original marshmallow candy from ancient Egypt, this recipe combines a traditional honey nougat and extract of the marshmallow plant. It is light, fluffy, and sweet, with a touch of earthy flavor.

Servings: 20 small pieces

Prep and cook time: literally an entire day

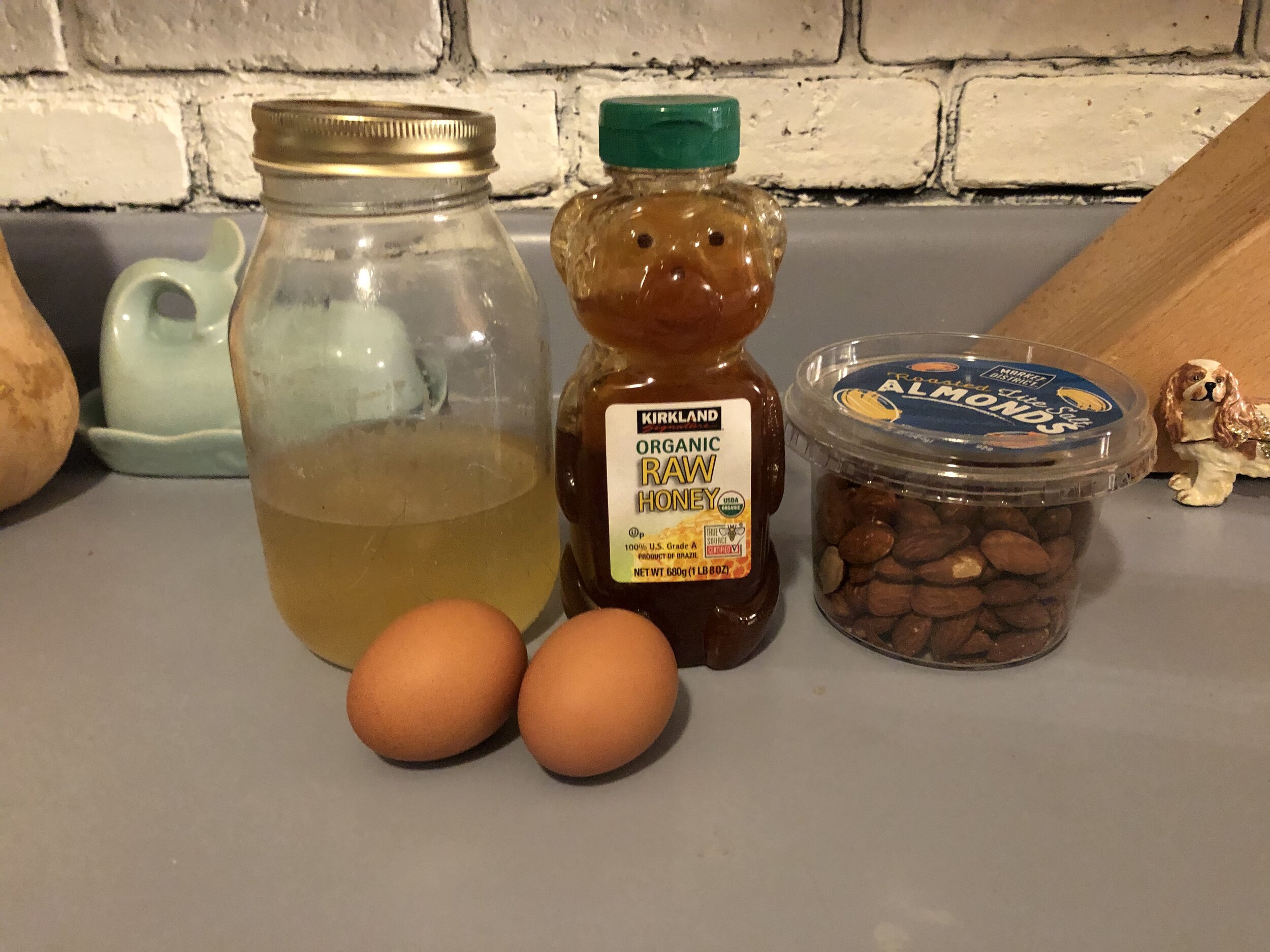

Ingredients:

1 Tbsp dried marshmallow root

1 Cup of water

½ lb honey

2 Egg whites

½ lb Nuts or dried fruit of choice, warmed

Instructions:

1. Combine 1 cup water and 1 tablespoon marshmallow root in a sealable jar. Let sit overnight, or for at least 12 hours. (Infusion will last in the fridge for at least 3 days.)

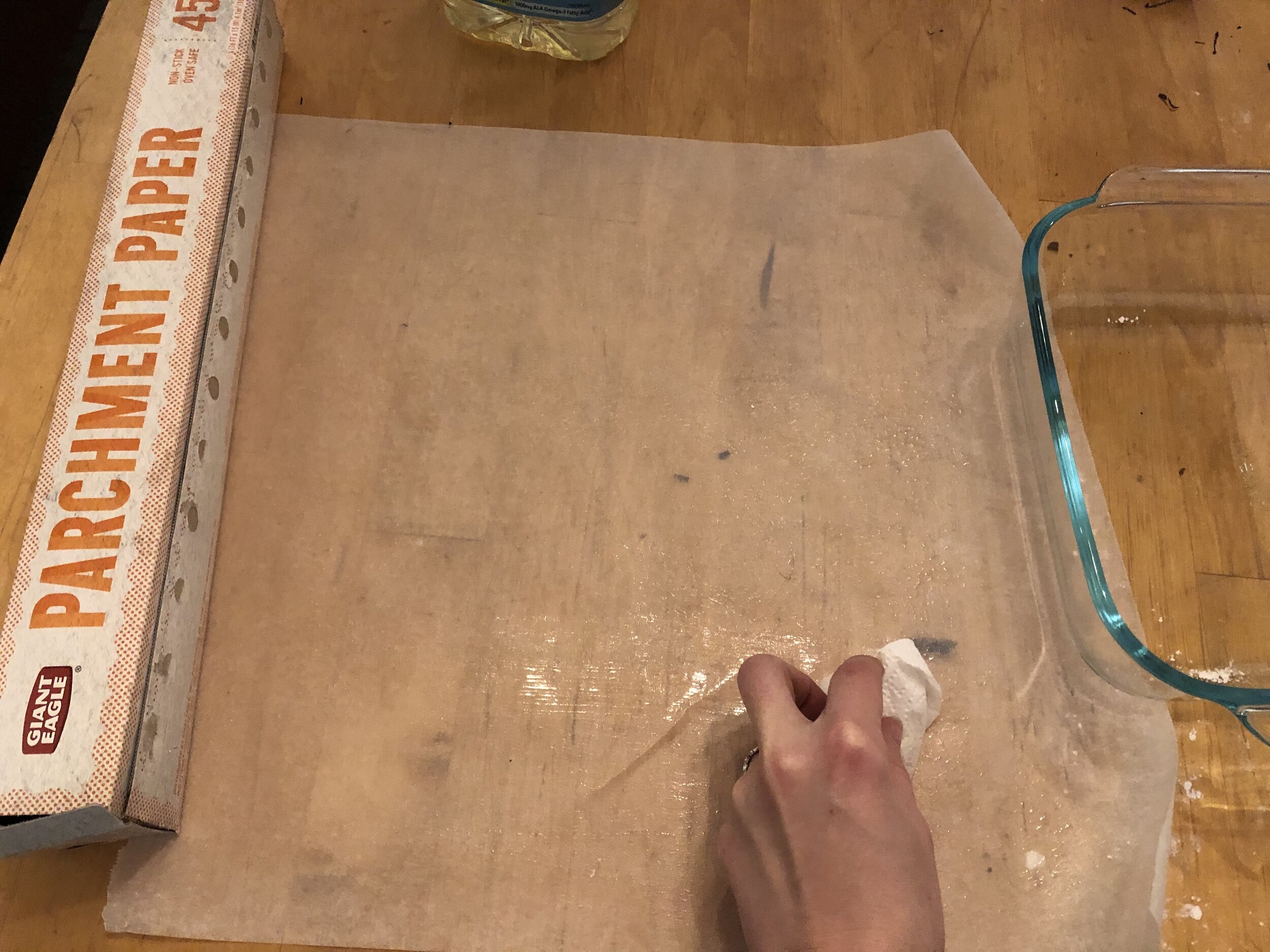

2. Prepare the pan. Line an 8”x8” baking tin with parchment paper. Grease the parchment paper, OR have a layer of powdered sugar, OR you can place a piece of edible wafer/rice paper on top of the parchment. (Note: this is NOT the same as rice paper wrappers.)

3. Strain your infusion through cheesecloth or through a loss leaf tea filter, removing all root solids.

4. Spread your mix-ins on a tray and place it in an oven at 250 to keep warm.

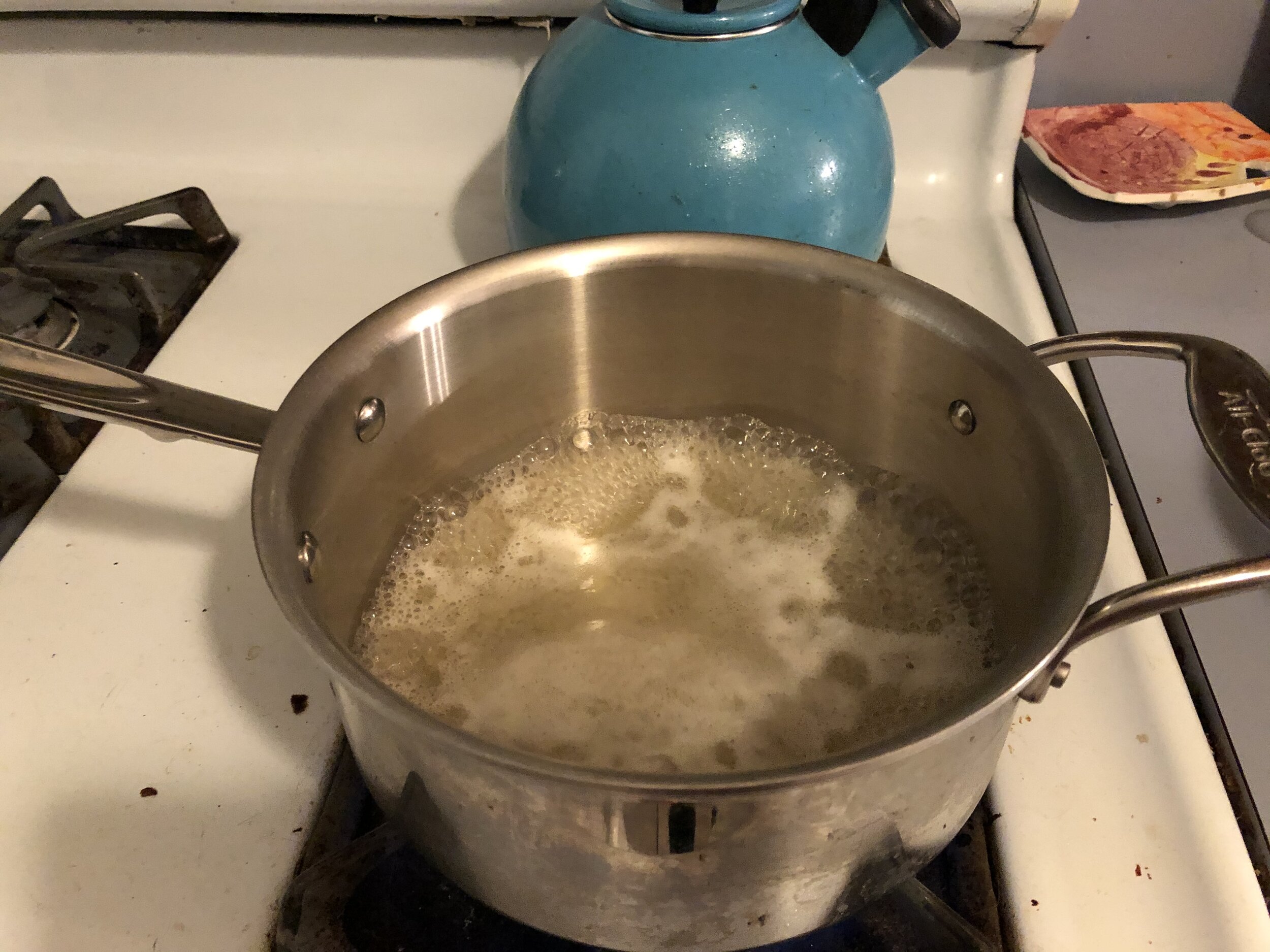

5. Place marshmallow infusion on the stovetop, and bring to a rolling boil on high to reduce some of the extracted liquid. This will take about 5 min.

6. Once the marshmallow extract is reduced, turn the heat down to medium-low and add your honey. Heat honey until it is completely liquid. (Note: This is a good recipe to use older honey that has started to crystallize, as you are heating it completely anyway.)

7. While honey is heating, separate your egg whites. (Note: I separated the egg whites, and froze the yolks to be used at a later date. Waste not, want not!)

8. Whip egg whites to soft peaks; set aside. I did this part by hand with a whisk, but feel free to use an electric beater.

9. Once the honey is completely liquefied, turn the heat down to low. Using your whisk, add in dollops of whipped egg whites, beating them in hot honey syrup to incorporate evenly. Continue until all egg whites are incorporated.

10. Using a wooden or silicone spatula, stir the mixture continuously on low for 45-50 minutes. The mixture will begin to thicken and hold its shape when stirred. Cook until a small amount of the mixture – maybe ½ teaspoon – holds its shape when dropped into a bowl of cold water.

11. Add the warmed nuts. The nuts must be warm, or your nougat will harden too quickly. Keep cooking for another 3-5 minutes, mixing ingredients in.

12. Remove pan from heat, and dump contents of the pot into your prepared tin.

13. Add another layer of greased parchment paper, or powdered sugar or wafer paper and another layer of parchment paper. Press down firmly, creating a smooth layer of nougat.

14. Let sit and cool for 2-3 hours.

15. Save until ready to ready to serve, then cut into squares and enjoy a treat of the ancient Egyptian royal court.